Our Heritage

A Journey Through Time

Two defining features of Crete – its geographical position and temperate climate – have shaped both the desires of its people and the ambitions of countless conquerors. Positioned at the crossroads of north, south, east and west, the island thrived as a hub of Mediterranean trade. Its mild climate, intense sunshine and fertile soils favoured the cultivation of the vine, a practice central to Crete’s history.

Bronze Age (2900 BC – 1100 BC)

Prehistoric Crete, home to the Minoans – the first true European civilisation – saw the introduction of viniculture, likely learned from the Egyptians. Unlike Egypt, where beer dominated, Crete’s rocky and mountainous terrain, mild climate, intense sunshine and sufficient rainfall, combined with its advanced navigation skills, encouraged the Minoans to make wine and export it to neighbouring peoples.

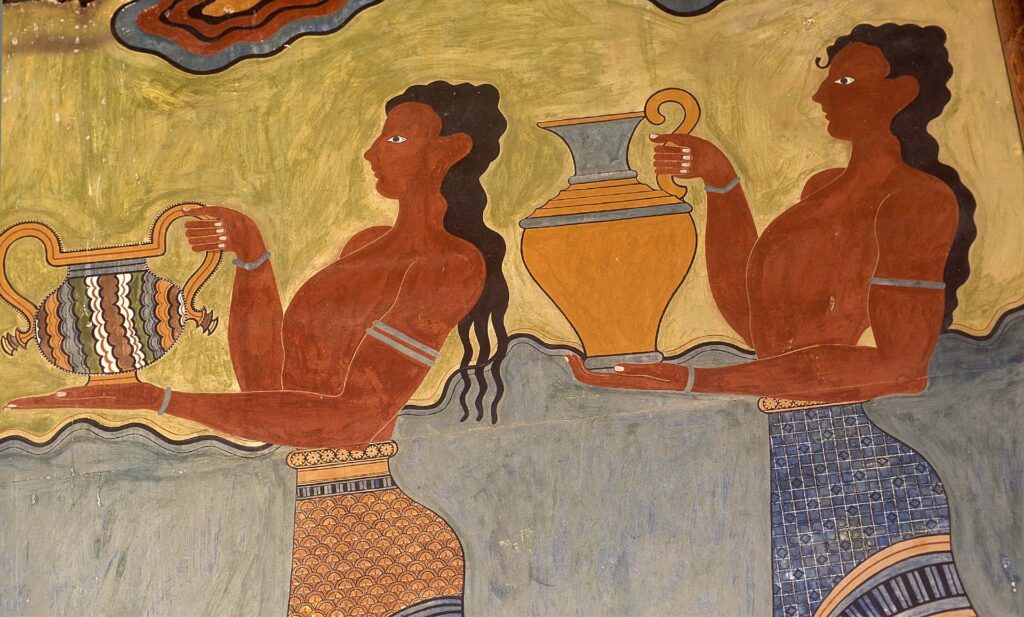

Archaeological finds – wine presses, vessels, Linear A and B inscriptions, and frescoes – confirm significant production, particularly in northern Crete near Knossos. Harvest coincided with the autumnal equinox and was a festive communal event. Farmers of all ages took part: some cut and carried grapes, others prepared food, and men treaded the grapes in clay presses requiring both strength and skill. Must was stored in sealed jars and transported in vessels or wineskins, often labelled with type and origin.

Wine permeated daily life, trade, and ritual, laying the foundation for Crete’s enduring viticultural tradition.

Antiquity (1100 BC – 30 BC)

The eruption of Thera around 1160 BC devastated Minoan civilisation. Dorian settlers brought military dominance but ongoing city-state wars and pirate raids hindered trade. Still, the Eteocretans preserved ancient customs, and vine cultivation continued, mainly for local consumption.

The Code of Gortyn, from the Hellenistic period, is the oldest surviving Greek legislation and includes rules on vine-growing, underscoring its importance.

Roman Empire (30 BC – 330 AD)

Crete’s incorporation into the Roman Empire marked a golden era for wine. Strategically located between Rome and Alexandria, the island became a vital link in Mediterranean trade. Peace, stability, and Roman passion for wine led to the rise of the celebrated “Sweet Cretan Wine.” Grapes were often sun-dried after harvest to concentrate sugars, yielding naturally strong, long-lasting wines ideal for export.

The winemaking craft evolved significantly, with improved pressing methods and careful maturation. Seventeen amphora workshops on the island supplied the vessels for shipping wine across the empire. Strict inspection mechanisms ensured quality and quantity, reflecting the high value placed on the product. This period cemented Crete’s reputation as a producer of refined wines appreciated far beyond its shores.

Byzantine Empire – 1st Period (330 AD – 824 AD)

Byzantine rule brought renewed growth. Christianity flourished, monasteries cultivated vineyards, and Saint Tryphon, patron saint of wine, was honoured. Wine played a central role in religious rites, medicine, and daily life, with monasteries preserving detailed regulations for its production and storage.

Arab Rule (824 AD – 961 AD)

Arab (Saracen) occupation marked a decline. Harsh rule, slavery, and piracy devastated the population and economy, including viticulture.

Byzantine Empire – 2nd Period (961 AD – 1204 AD)

The Byzantines’ return brought stability and a revival of vine cultivation. Christianity’s deep symbolism of the vine was reflected in every art form – from church frescoes and stone reliefs to wood carvings and vestments. These images reveal that viticulture was not merely agricultural labour but a spiritual and cultural symbol of renewal, abundance, and faith, woven into the identity of the island.

Venetian Period (1204 AD – 1669 AD)

Perhaps the most glorious age for Cretan wine. Vineyards spread across all classes, and wine was more profitable than cereals. The Venetians, master traders, exported Cretan wine across Europe, stimulating constant improvement in quality and yield.

Winepresses from this period, many still standing in the Peza zone, were feats of practical design. Usually built by feudal lords, they often featured a domed porous stone press connected by limestone pipe to a collection vat. Positioned on slopes, they used gravity to channel must into vessels for transport. Carved channels and openings (“anemolaos”) allowed for ventilation and efficient collection.

Cultivation practices were carefully regulated – pruning, digging, protecting vineyard boundaries, and renewing vines – ensuring a product worthy of Venice’s high standards. Wine prices depended on type, origin, age, and transport conditions, with detailed contracts preventing adulteration. This period firmly established Crete’s wines in the consciousness of Europe.

Ottoman Empire (1669 AD – 1898 AD)

Ottoman rule proved disastrous for viniculture. Religious prohibitions, punitive taxes, and neglect led to vineyard destruction and decline in quality. Crete’s economy and culture suffered, though rural families maintained small-scale production for their own needs, keeping traditions alive.

Modern Greece (1898 AD – Today)

With liberation and union with Greece in 1913, Crete began reviving its vineyards. Recording local varieties, professionalising oenology, and founding wine institutes laid the groundwork for recovery.

After setbacks from wars and phylloxera, the 1960s marked a rebirth. Legislation protecting origin and quality (PDO) revived indigenous varieties. Modern technology, rediscovery of forgotten grapes, and skilled local winemakers have restored Crete’s reputation for fine wines.

PDO Peza

Located in central-northern Heraklion, the PDO Peza zone – recognised for reds in 1971 and whites in 1982 – covers villages such as Peza, Katalagari, and Myrtia. Vineyards lie between 300 and 800 meters on calcareous soils, sheltered from hot southern winds by mountains, and cooled by northern breezes for gradual maturation.

Reds traditionally blend 75% Kotsifali with 25% Mandilaria, the latter adding structure and colour. Nine wineries produce PDO Peza reds, while five produce whites, each expressing the zone’s unique terroir.